The Uncanny Valley of Information (from AI)

How AI creates believable fictions, why it won't stop, and why conversational refinement is our best tool for improvement

Christian J. Ward

Sep 29, 2025

AI makes it incredibly hard to spot

We have been conditioned for generations to accept convincing narratives, starting when marketing made it hard to spot truthfulness.

Then, politics made it difficult to discern morality, and social media made it challenging to distinguish reality.

Now, AI makes it difficult to spot simple mistakes because it packages them so beautifully.

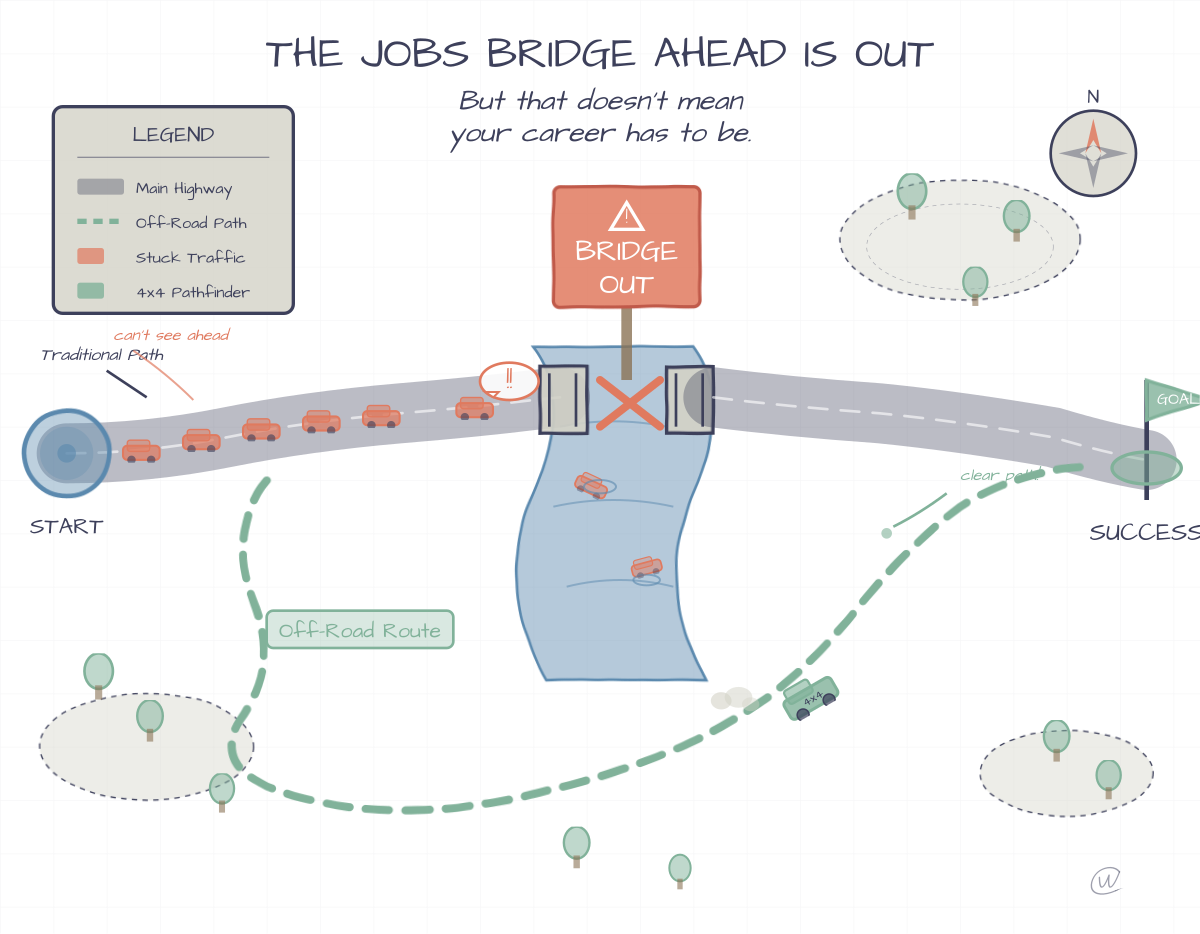

This progression follows a technological version of the uncanny valley. I'm often surprised by how early CGI looked so terrible, but at the time, I can't say I didn't just immerse myself in the experience anyway. The flaws only become apparent with distance and hindsight.

I was re-watching Tron (1982) with my son, and I remember seeing some of the first CGI in that film. Sure, it's dated now, but wow, was it real to me as a kid.

The core issue is that humans tend to want to believe what they see, and this is a fundamental problem as these technologies improve at generating believable fictions.

A History of Plausible Deception

The path from marketing to AI is a clear one. Seth Godin’s book, All Marketers Are Liars, has excellent examples of how marketing works by telling stories that people want to believe, not by stating objective facts.

I had the honor to interview Seth Godin twice on different Yext Podcasts, and he has always been a source of great wisdom about marketing, audience, and the incredible power of purpose. (Podcast below, from 2021, to discuss Minimum Viable Audiences - something every newsletter like mine ascribes to.)

Overall, the concept of truthfulness became secondary to building a compelling narrative that aligned with a person's worldview.

AI will, unfortunately, accelerate this in its early stages of adoption.

Politics took this a step

Each of these social constructs moved us further from a shared, verifiable truth and closer to a reality defined by what feels right or what causes the least discomfort.

This has created an uncanny valley of information.

Just as near-human robots can be unsettling, information that is almost perfect is harder to critique than information that is obviously flawed. We've been trained for years to accept these convincing fictions, and AI is the ultimate fiction generator, making the uncanny valley wider and deeper than ever before.

Uncanny Human Likeness - but in text & image recognition

We May Never Have Perfect Output, and a New Paper Explains Why

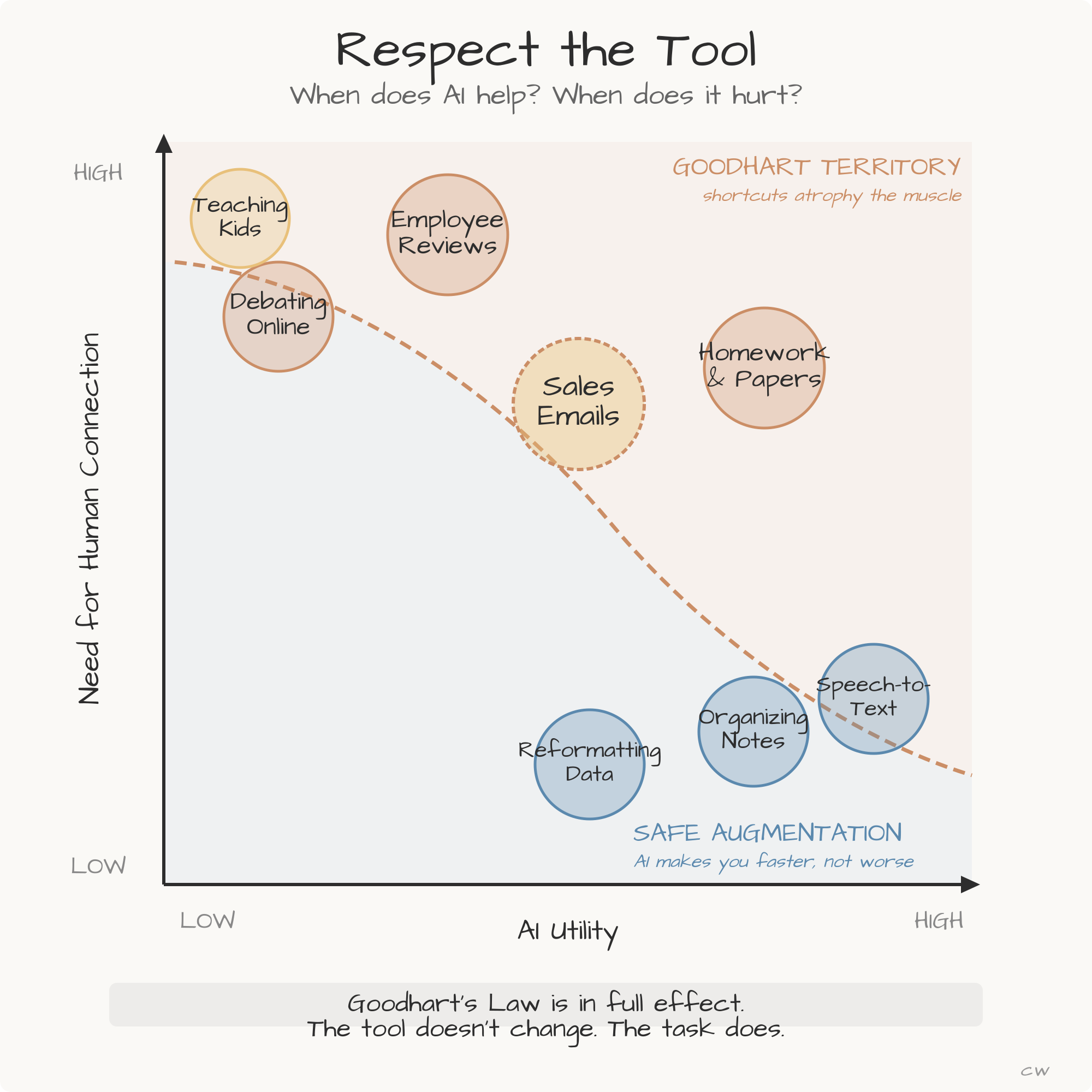

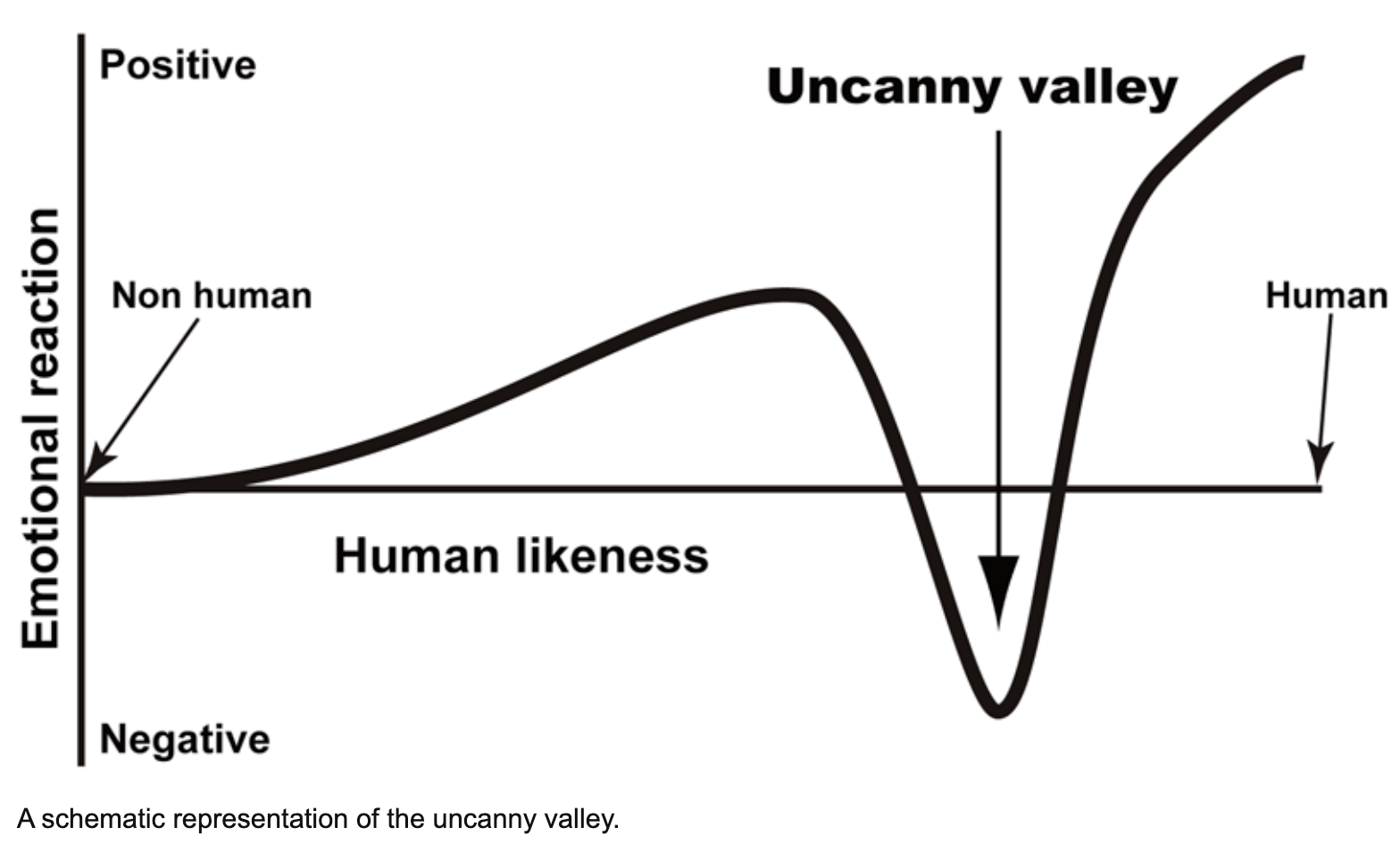

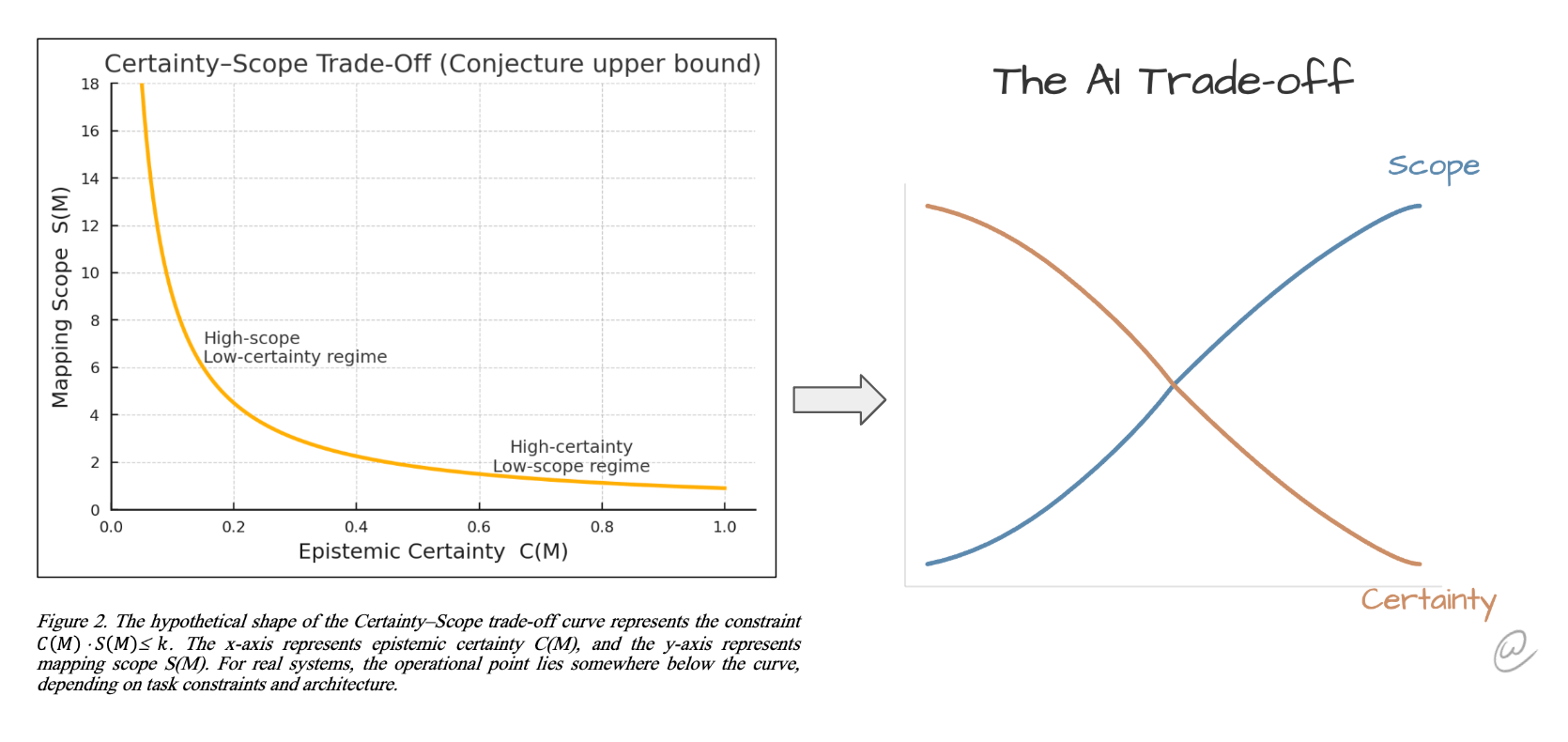

The issue of AI producing convincing falsehoods may not simply be a temporary bug to be fixed, but a fundamental characteristic of how these systems operate. A new paper from Luciano Floridi at Yale University, titled "A Conjecture on a Fundamental Trade-off between Certainty and Scope in Symbolic and Generative AI," formalizes this very idea.

The core of the conjecture is that there is an inescapable trade-off between an AI's provable correctness (its certainty) and the informational breadth of the tasks it can handle (its scope).

High-Certainty, Low-Scope: Think of a simple calculator. Its scope is incredibly narrow; it only handles basic arithmetic. Because of this narrow focus, it can achieve perfect, provable certainty. Its answers are always correct.

High-Scope, Low-Certainty: Now, consider a large language model, such as GPT-4. Its scope is vast. It can process and generate information on nearly any topic, from writing poetry to explaining complex concepts like quantum physics. According to Floridi's conjecture, because its scope is so large, it must relinquish the possibility of guaranteed correctness.

There is an "irreducible risk of errors." - This is the conjecture.

This trade-off can be visualized as a curve that any real-world AI system must operate under.

This is why we can’t have nice things (in AI output).

As the chart shows, to gain more certainty and move to the right, an AI's operational scope must shrink dramatically. Conversely, to achieve a massive scope like today's generative models, we must accept a lower level of certainty.

This formalizes why AI is so good at making "garbage sound like the truth." It's operating in a high-scope regime where a certain level of error is not just possible, but a mathematical necessity. This reframes our expectations, suggesting we may never engineer a generative AI that is both all-knowing and always right.

The full paper can be found here:

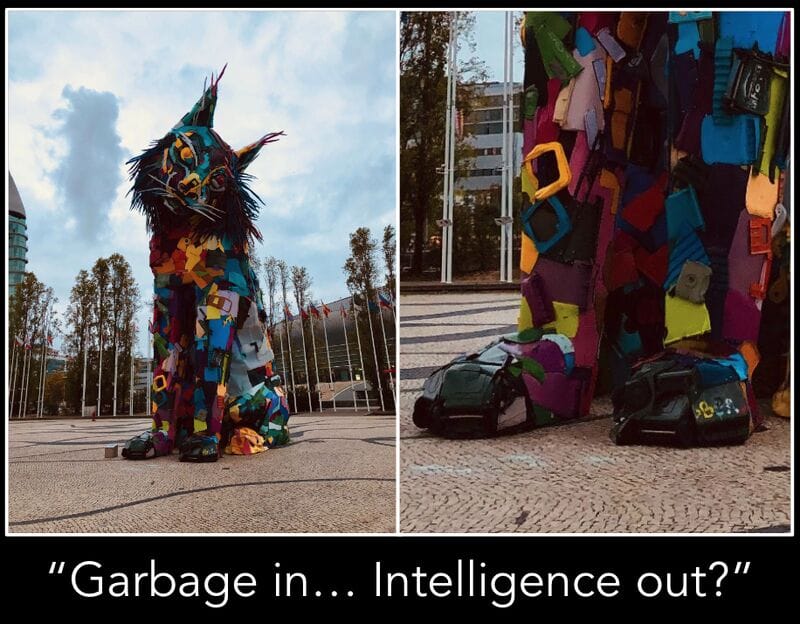

Garbage In, Intelligence Out?

People often repeat the mantra "garbage in, garbage out" when talking about data systems, but AI challenges this assumption. If you ever travel to Portugal, there is an excellent artist who defies the “garbage in, garbage out” approach by turning garbage into amazing animals all over Lisbon. They’re called the “Big Trash Animals”.

AI takes Garbage and turns it into believable Content.

I believe the artist Bordalo II embodies this new reality. He takes literal

Spotting them requires a level of scrutiny that most people are not prepared to apply, especially when the output confirms what they already believe.

What Can be Done? Context through Conversations

What Can Be Done

While an AI can produce a flawed but confident answer from a vague prompt, we have a powerful tool to improve the result: conversation.

The key is to reduce the scope of the inquiry. By treating the interaction as a dialogue rather than a single command, you can quickly refine the AI’s focus. The initial output may not be perfect, but it serves as a starting point that improves significantly as you provide more context.

I have noticed that, with my use of voice, it is much easier to have a dialogue to narrow down what you are focused on with the large language model.

This process doesn't eliminate the randomness in the output, but it guides the system toward far better solutions by dramatically narrowing the problem space. You can turn a generic answer into a more specific and useful one.

The future is conversational because dialogue is our best tool for clarification. This is why I'm such a fan of prompt inversion, where the AI asks you clarifying questions. This process happens so much more naturally conversationally than it does through typing. Reid Hoffman called it getting "voicepilled," using the red pill analogy from the Matrix, where you finally start using voice to fully converse with the AI.

He was blown away by it.

“Welcome to the party, pal!” - John McClane

I've been using voice for a few years now, and the added capability from using ChatGPT and Gemini's voice features is immense.

Claude still isn't there because you still have to tap it to continue a conversation.

But the seamless back-and-forth dialogue is where these systems gain the context they need to produce more accurate and helpful results. As I wrote about in last week's blog post, the advancement in Chrome for AI from Gemini, where you can “go live” and talk to your browser, is an excellent demonstration of where this technology is headed.

We Want to Be Fooled

We have a lot of work to do when it comes to trust.

The fact that AI can turn garbage into something indistinguishable from the truth is a problem that will only be overcome in time.

And if I'm being totally honest, I'm not sure humanity is really equipped for this.

If you think about the history of things that have constantly fooled us, part of it is that we want to be fooled. We want to believe the compelling story, the easy answer, the beautiful sculpture made of junk.

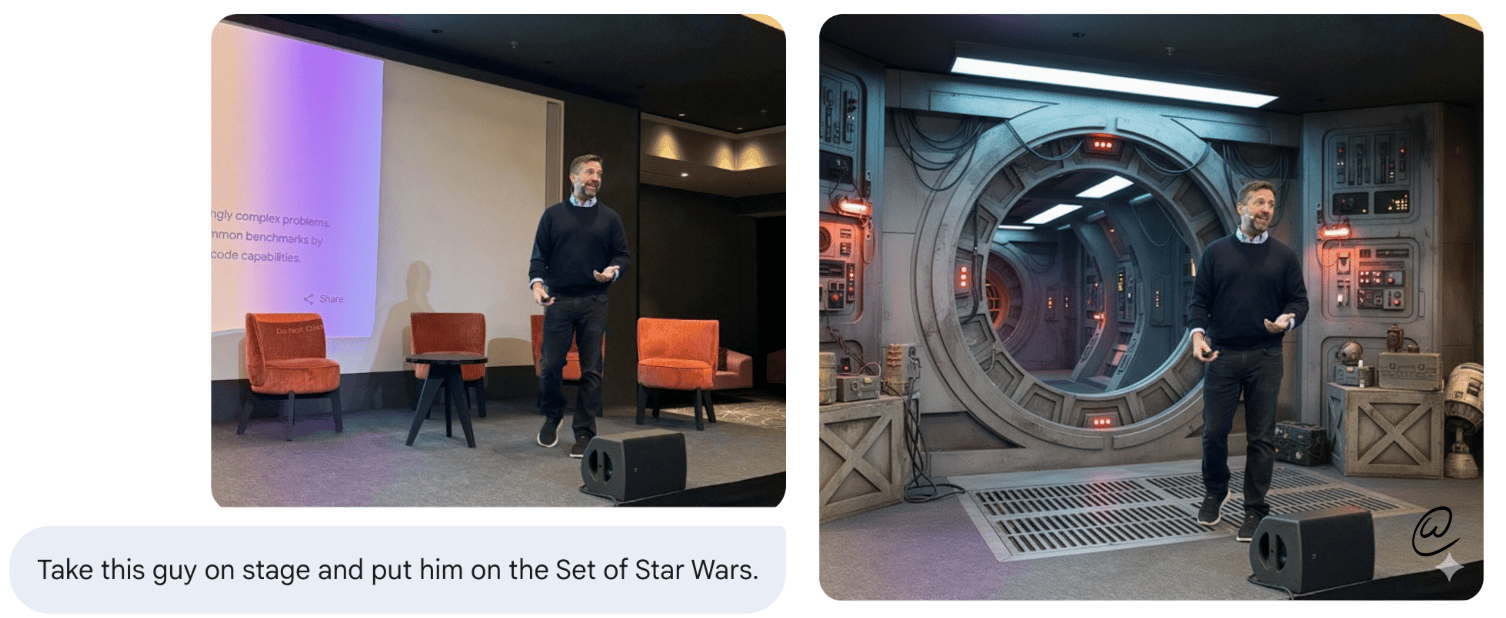

We willingly suspend our disbelief for the sake of the experience. Google's image generation model, called Nano Banana, makes this incredibly easy. You can take a photo of someone on a boring stage (giving a boring speech) and, with a simple prompt, place them on the set of Star Wars.

The result is seamless and believable, and our brains readily accept it.

Rogue None. Yes, Photoshop could do this - but I wouldn’t know how.

The problem is that AI operates in areas where suspending disbelief can have serious consequences. As I wrote about before, being more disagreeable is a trait that really helps when people try to market to you, politicize things, or convince you with fake AI content.

In these systems, disagreeableness gives you an advantage.