The AI Cyrano Effect

When Everyone Sounds Brilliant, How Do You Know Who Actually Understands Anything?

Christian J. Ward

Jan 5, 2026

In the 1970s, psychologist Stanley Milgram ran one of his lesser-known experiments. He placed hidden earpieces on participants and fed them words to speak in real-time during conversations with strangers. The strangers never detected the deception. Milgram called this the "cyranic illusion," named after Cyrano de Bergerac, the 17th-century playwright famous for secretly feeding romantic lines to a handsome but dull suitor.

The implications were unsettling. People consistently failed to notice when the person across from them was merely a vessel for someone else's thoughts. The physical presence of a body created an automatic assumption of mental presence.

We are about to experience this at a civilizational scale.

A Guardian investigation months back found that nearly 7,000 UK university students were caught cheating using AI in the 2023-24 academic year. Experts say this represents the tip of the iceberg. More than a quarter of responding universities did not even record AI misuse as a separate category of misconduct.

My daughters (high school and college age) confirm that the amount of cheating on exams with AI is insane. I don’t even know what the point of online exams is at this point. We should be racing back to hand-written, in-person testing and throw multiple-choice exams away. I blame multiple-choice testing for much of the collapse of education anyway.

This is where we are now. Not where we will be heading through 2026.

Knowledge Without Understanding

Years ago, someone gave me a sign that read: "I can explain it to you, but I can't understand it for you."

The difference between knowledge and understanding has never mattered more.

AI may not understand it for you either.

AI gives everyone access to knowledge. Type eight words into ChatGPT and receive a 900-word treatise on why one business strategy outperforms another. The output sounds authoritative. It includes caveats and nuance.

It might even be correct.

But the person who prompted it may have no idea whether the reasoning holds. They cannot defend the argument in follow-up questions. They cannot apply the principles to novel situations.

They have knowledge without understanding, and there is no way for you to tell the difference from the output alone.

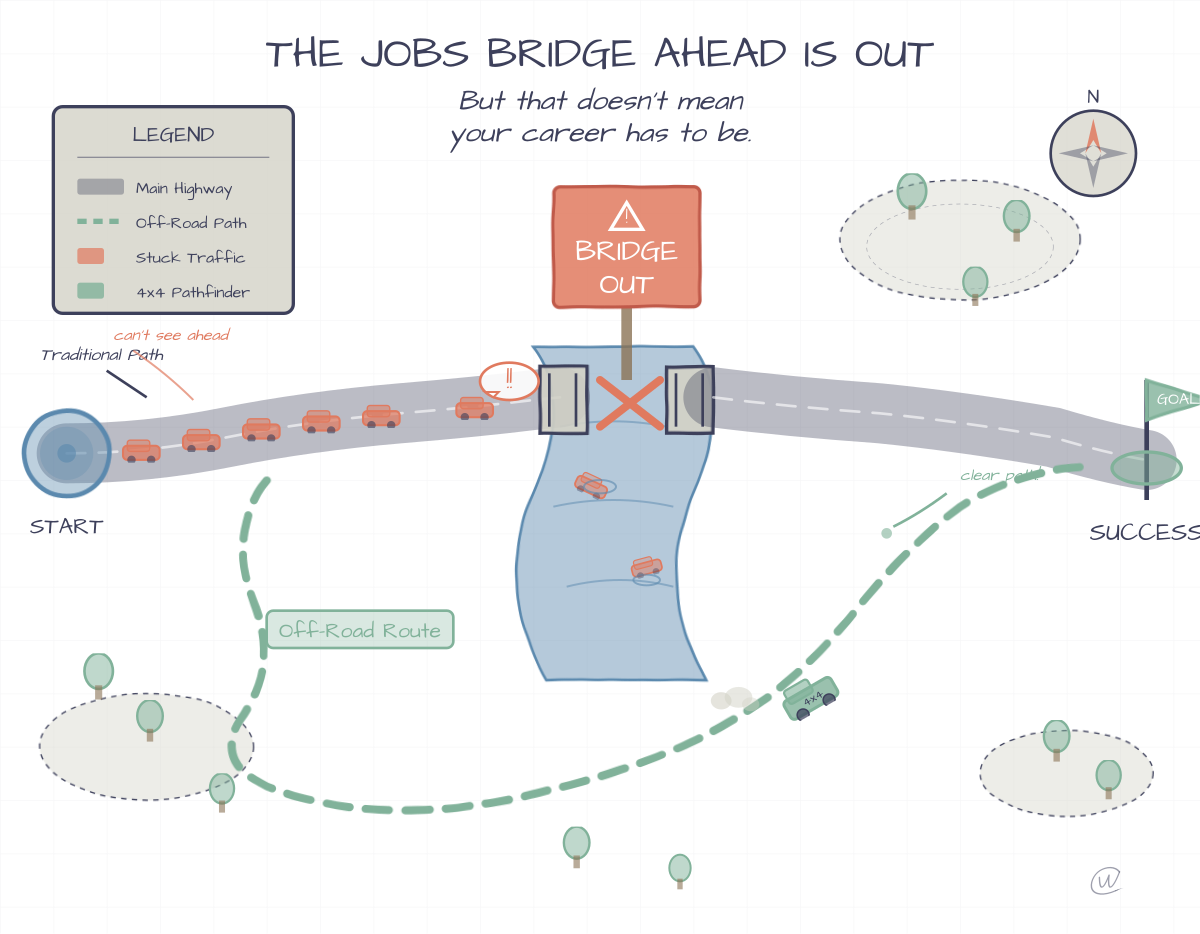

I wrote about the transition from the Brawn Age to the Brain Age to the Backbone Age last year. Physical strength dominated until machines filled that gap. Cognitive ability dominated until AI began to fill that gap.

Now we enter a period where the willingness to think independently and challenge consensus becomes a scarce resource.

But there is a corollary I did not fully explore: what happens when AI makes everyone sound equally intelligent?

The Extended Mind Problem

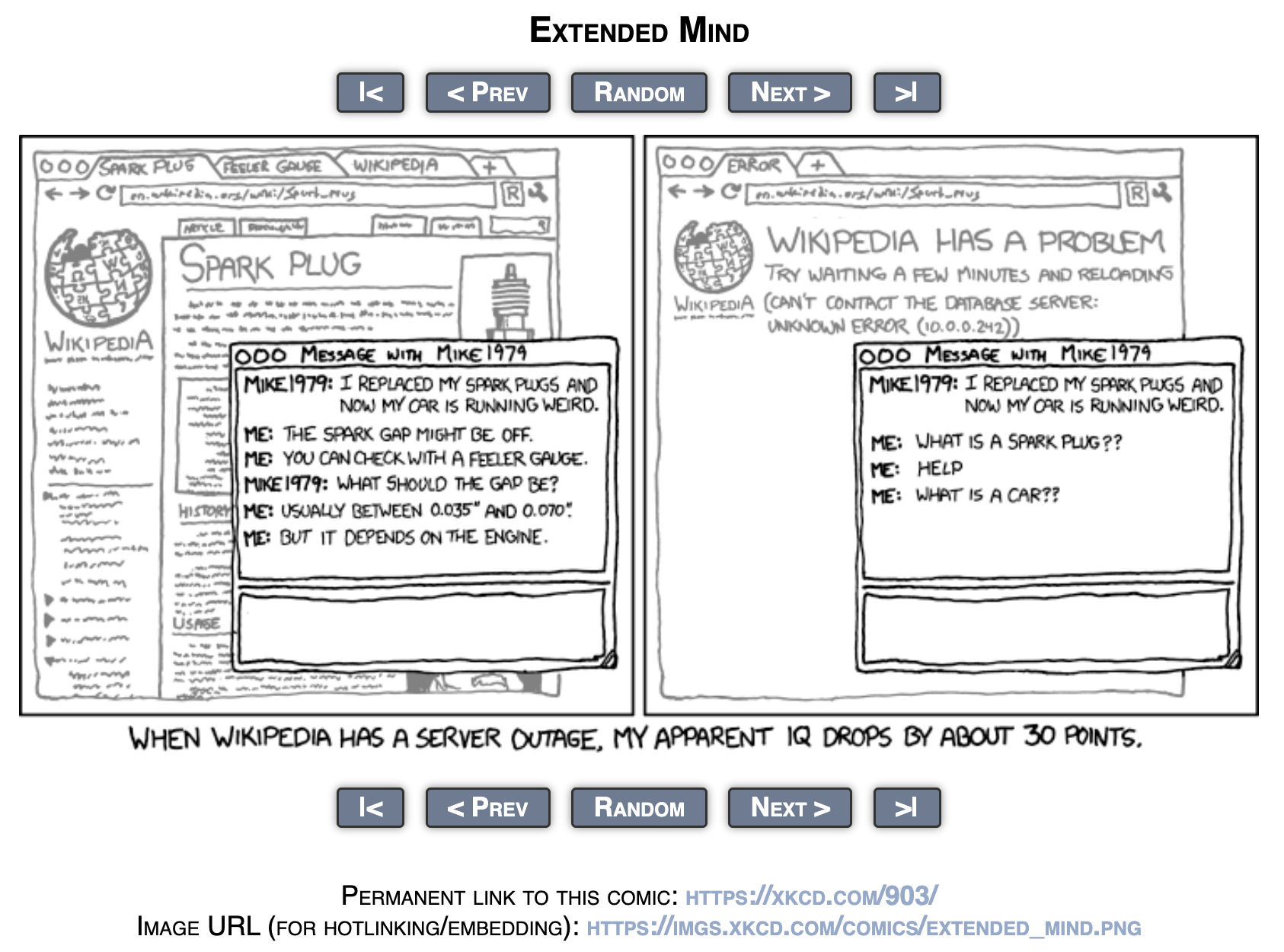

Randall Munroe captured this perfectly in his XKCD comic "Extended Mind" years ago.

The comic shows someone confidently helping a friend troubleshoot spark plugs while browsing Wikipedia. In the next panel, Wikipedia goes down, and the same person types: "What is a spark plug?? HELP. What is a car??"

The punchline. "When Wikipedia has a server outage, my apparent IQ drops by about 30 points."

That was funny in the Wikipedia era. It is less funny now.

With AI always available, the IQ boost is not 30 points. It might be 50. Or 80.

And unlike Wikipedia, AI does not just retrieve facts. It synthesizes arguments, writes persuasively, and mimics expertise across any domain.

The person you are messaging, the author of that LinkedIn post, the job candidate who aced the written assessment, they might have the equivalent of Milgram's hidden earpiece. An AI feeding them every word.

And just like Milgram's subjects, you probably will not detect it.

The progression looks something like this: a modest knowledge boost in the pre-Internet era, a significant jump once Wikipedia put encyclopedic knowledge in everyone's pocket, and now an exponential leap as AI can synthesize, argue, and write on your behalf.

The middle one is Steve Martin in Roxanne.

The Pollution Problem

I have written extensively about AI slop, the flood of generic AI-generated content polluting the internet. But the Cyrano Effect is different.

Slop is obviously low quality. The Cyrano Effect produces content that appears high-quality because it is genuinely well-written.

Look at YouTube comments. LinkedIn posts. Twitter threads. More and more of what you read is AI-generated, but it does not read like spam. It reads like someone thoughtful took time to craft a nuanced response.

The problem is that the person may have typed a single sentence and let the AI do the rest.

This creates an authenticity crisis that is harder to solve than spam filters. You cannot detect it algorithmically because the content is legitimately good.

You can only detect it through extended interaction, by probing the gaps between what someone wrote and what they actually understand.

What 2026 Looks Like

I think 2026 will be the year this becomes impossible to ignore.

Gemini will be baked into everything Google touches. Traditional Google search, as we know it, will not disappear, but more users will default to conversational AI queries. When you type or speak a question in natural language, the AI version will handle it better than a keyword search.

Google will likely count the downstream searches that fan out from a single Gemini conversation. One prompt might trigger 20 to 200 background searches. They will report this as "search volume increasing" when, in fact, users are spending a fraction of the time they used to.

The metrics we use to measure search and AI adoption are wrong. The number of searches is a meaningless statistic.

What matters is the time spent in each application and the time saved. Those are hard to measure, but they are the right way to think about what is happening.

Meanwhile, the Cyrano Effect will accelerate. Everything online will sound more knowledgeable than it did in 2025, which sounded more knowledgeable than it did in 2024. The people producing this content may understand less and less of what they are putting out.

The In-Person Advantage (For Now)

Milgram's original experiments proved that face-to-face deception is absolutely possible. His subjects spoke words fed through hidden earpieces while sitting directly across from people who never suspected a thing.

The technology to replicate this with AI is not far off. Bone conduction devices already allow people to hear audio through their jawbone without anyone else detecting it. Pair that with a real-time AI assistant, and you have the makings of a modern cyranoid.

But here in early 2026, we are not quite there yet. The latency is still too high. The coordination is still too clumsy.

For now, real-time face-to-face conversation remains one of the few reliable ways to gauge whether someone actually understands what they are talking about.

In a meeting, you can probe understanding with follow-up questions. You can watch someone think through a problem without the buffer of typing time. You can sense hesitation, confusion, or confidence in ways that text strips away.

This is why in-person interaction is making a comeback in certain industries. Not because remote work failed, but because verifying competence requires unscripted, real-time exchange.

I actually think this is good news for humans. After years of being forced inside, stuck on Zoom calls, reduced to faces in boxes, we may be rediscovering something important. Being Present.

This will not last forever.

But for now, there is a window where showing up in person and thinking out loud still means something.

Standing By Your Words

I have adjusted my own workflow to address this. Most of my prompts explicitly tell AI to use 90% of my exact words, only cleaning up filler and mistakes. I talk to the machine more than I type.

The voice is mine. The AI is an editor, not an author.

Could I let the AI improve my writing significantly? Absolutely. It would probably make me sound smarter, more polished, more authoritative.

But then I would be contributing to the very problem I am describing. The gap between what I sound like and what I actually understand would widen.

I am not claiming to be smart. I am claiming to be present.

When you read my words, you are getting my actual thinking, with all its limitations. If you probe my arguments, I can defend them, not because I am a wizard, but because I actually wrote them.

I think more people will start doing something similar. Attaching their transcripts. Sharing their drafts. Finding ways to signal that the person behind the words actually understands them.

In a world where AI can make anyone sound brilliant, the new differentiator might simply be authenticity.

Related: The Disagreeable Advantage | AI Slop Is Marketing's Latest Victim